back to WRITINGS

Freedom via Soft Order - Architecture as a Foil for Social Self-organisation

Patrik Schumacher, London 2018

Published: AD Architecture and Freedom, Guest Edited by Owen Hopkins,

Architectural Design,May/June 2018, Profile No.253, Wiley

Freedom as theme within architecture starts with the modern movement: the free plan, the free façade, the free flowing space. The theme got another boost in the 1960s and 1970s in connection with the emancipatory thrust of counter-culture movements and was expressed in the pursuit of lightness and flexibility via spaceframes, capsules, inflatables, instant architecture1, play-scapes and the informality of adhocism2. However, progressive liberation experienced disillusionment, both within architecture and within society at large. It is my contention here that now the expansion of freedom can get a viable new lease of life, both in contemporary society and in its architecture, via libertarianism and parametricism.

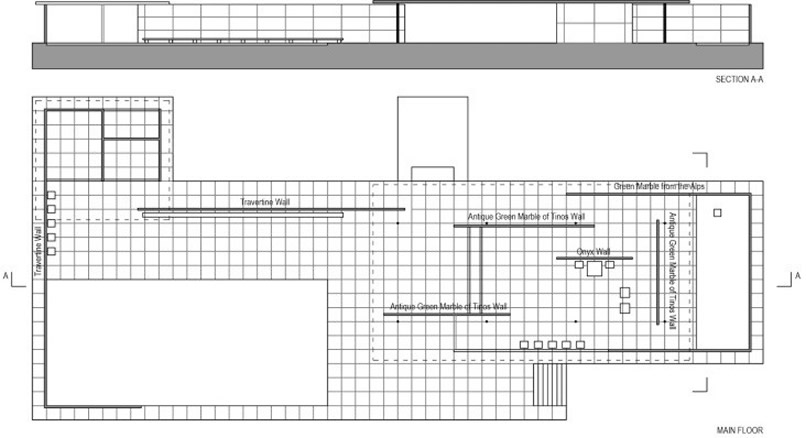

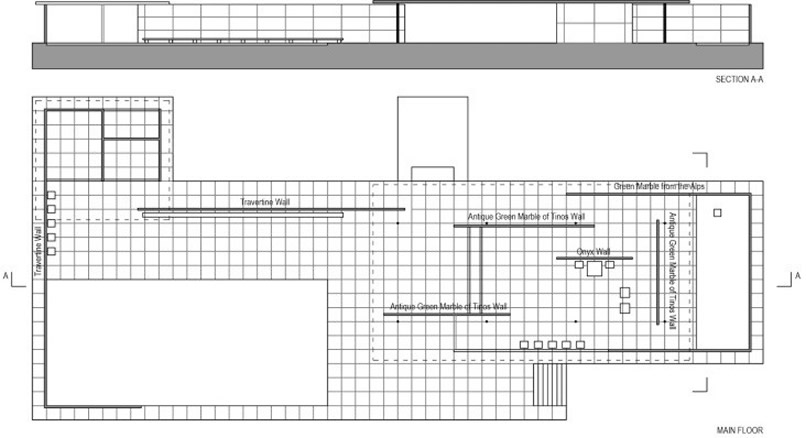

Mies van der Rohe, Barcelona Pavilion, 1929. Modernism set architecture free from archetypes via abstraction, implying free composition without the strictures of symmetry and proportion, set walls and envelope free from structural loads (free plan, free facade), and promoted a free flowing space.

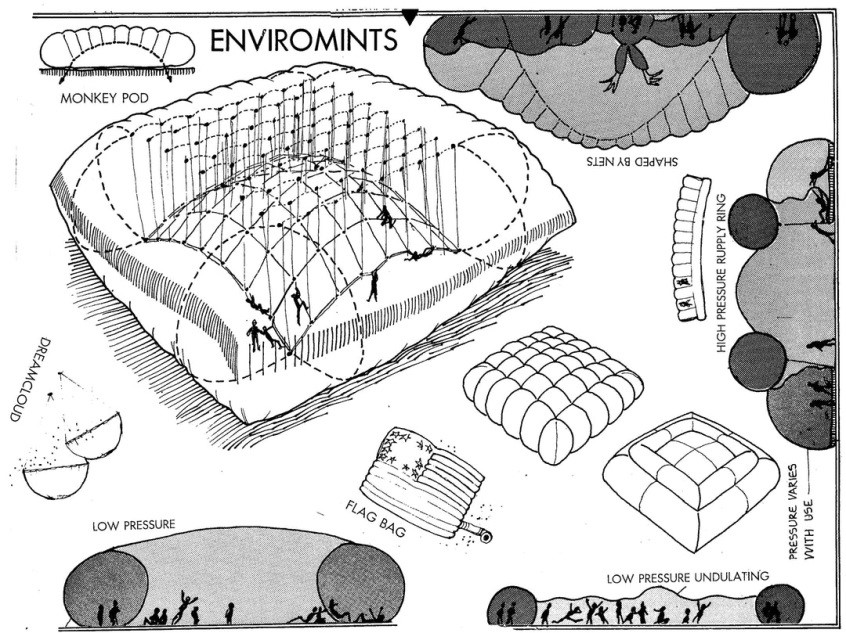

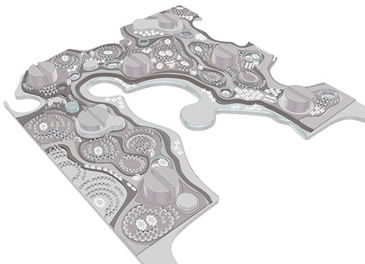

Antfarm, Page from the “Inflatocookbook”, 1971. The 1960s seemed to promise technological utopias where the city was conceived as a free-wheeling play-scape for life beyond scarcity of a posited ‘homo ludens’ engaged in playful creative self-transcendence.

Life, Freedom, Foresight and Economy

Freedom is our penultimate value, the condition and aim of all human strivings. As living systems we strive to maintain ourselves and this implies maintaining the degrees of freedom we have attained in order to chart a safe passage through an indifferent and often dangerous physical world. From Daniel Dennett we can learn the most basic definition of freedom as it emerges in the evolution of living systems. The beginning of freedom of action is the avoidance of danger and the most basic move of a self-preserving living creature is to move out of harm’s way. The more moves the creature can make, i.e. the more degrees of freedom the creature acquires, but also the more these moves are related to information-based anticipations, the greater are the creature’s chances to persist and reproduce. Freedom is advantageous and most sentient creatures instinctively resist shackles and controls. However, the above caveat about information-based anticipations must be remembered also. It implies that regularity and thus predictability are advantageous environmental features. The instincts of domesticated animals adapt to their more controlled and more predictable environment. As Dennett reminds us, “in a totally chaotic, unpredictable environment, there is no hope of avoidance except sheer blind luck.”3

Freedom must be coupled with foresight, and freedom to act crucially includes freedom to plan and prepare and indeed to labour so as to make the environment more hospitable and predictable. This implies the self-binding of actions as part of a planned, goal-oriented concatenation of actions, and requires self-discipline. The freedom to act becomes the freedom to pursue projects. The means for preparing, safeguarding and improving our inherently problematic survival are always scarce. Scarcity and thus economy remain ineradicable aspects of the human condition. Both individually and socially we are compelled to economize our time, effort and resources.

Freedom and Society

Our ancestors discovered, more by chance rather than by insight, that social cooperation and organisation (beyond the small size of primate groups) offer momentous productivity advantages that can make our path through the world much more secure, and potentially much more comfortable. The economist Ludwig von Mises emphasises the power of social cooperation in his formulation of the ‘law of society formation’4. Mises’ fundamental economic law generalises David Ricardo’s classic free trade law, the ‘law of comparative advantage’, and states that social cooperation via division of labour and exchange is always mutually advantageous, no matter how abilities, skills and resources are distributed, i.e. cooperation remains mutually advantageous even if one of the two parties concerned concentrates all skill and resource advantages on its side, as the cooperative division of labour allows the more productive party to concentrate its effort where its advantage is most momentous. The formation of ever larger societies with their attendant increase in social cooperation thus points the way towards greater emancipation from the burdens and threats of the physical world, thus representing a potential gain in physical freedom. However, societal organisation also implies rules and strictures that, at least prima facie, constrain freedom. Thus a new battle front for the striving of freedom has opened up: emancipation from societal strictures. Disputes about what constitutes necessary versus unnecessary, or even oppressive, societal restrictions have become a permanent part of the human condition and of our interminable striving for freedom. Our striving has thus become a complicated double agenda - physical emancipation and social emancipation - whereby the two sub-agendas often appear to conflict, with the additional complication that societal arrangements that seem globally advantageous are nevertheless differentially taxing to different members or groups within society. If we add to this the difficulties of transitioning from one societal regime to another, we can see the overwhelming difficulties that politics and political theory have to contend with. Global, sustainable freedom is thus hardly a simple matter. And yet, at the individual level it seems clear enough what would constitute an increase or decrease in one’s freedom.

Architecture as Medium of Societal Evolution

The initial formation of human societies was the unique take-off point for an accelerated evolutionary trajectory that has ushered in the Anthropocene and our current global civilisation. Architecture in the general sense of an artificial built environment was (and remains) an indispensable factor in establishing this new type of evolution: societal evolution. There is no human community without an artificially designed environment. It is the built environment that provides societal evolution with the cross-generational, material substrate by means of which an advantageous social order can persist and grow. Human settlements form ever larger and more differentiated spatio-material structures, as the skeleton for increasingly complex social structures. Architecture’s most profound achievement is thus not the oft-invoked protection from the elements, but an organisational achievement: social order. This pertains not only to the take off point of cultural evolution – our escape from the animal kingdom - but still applies in relation to the developmental tasks facing us today.

Architecture facilitates social order. The societal function of architecture is the organisation and stabilisation of social cooperation via the territorialising differentiation of activities and persons. This function is a universal necessity of all social formations and includes social control via discriminatory access restrictions as an inevitable feature of any spatialized social order. These restrictions might be posited by a central territorial authority or in a decentralised way by the several land owners, or their lease holders, in a society based on private property. In the classical liberal conception of society, as expressed in John Locke’s political writings, organized authority was to be based on the rule of law and charged with the protection of life, liberty, and property, conceived as natural rights. To hold onto and freely dispose over one’s homesteaded or rightfully acquired property was seen as a fundamental right and the property itself as an indispensable source of individual autonomy and freedom. The boundary lines that establish property demarcations are at the root of any architectural ontology. The owners have a protected freedom (and thus predictability) within these bounds and are thereby free to limit and regulate the degrees of freedom of all others invited into the territory for whom, however, both freedom and predictability are potentially reduced. In modern societies authority is much more centralized and the rights/freedoms of owners versus non-owners have been re-distributed away from owners. In the recent decades of the neo-liberal revolution the pendulum has swung back somewhat. The question whether overall societal freedom and capacity to innovate have been enhanced or reduced by these regime shifts remains a controversial issue and depends on one’s appraisal of the relative information processing and rational decision making capacity of market processes versus political processes. In my appraisal this depends on shifting historical technological conditions which can at least partially explain these regime shifts as rational adaptations.

Going forward I would advocate a further, more radical privatization trajectory, beyond neo-liberalism towards anarcho-capitalism, further empowering individual freedoms and market rationality while disempowering political processes. This appraisal is considering the unprecedented variation and innovation potentials opened up by the digital revolution and in this context motivated primarily by the markets’ superior information processing ability due to its parallel processing power. We should be able to expect that unleashing freedom in the form of entrepreneurial creativity would allow for the utilization of the market process as fertile discovery process in this new environment ripe with innovation potential. There no reason to expect that further privatization will lead to a situation where parts of society remain excluded or not catered for. The Sunday speech dream of a city where everything is totally inclusive is a deluded chimera. What can emerge instead under a new regime – the regime of libertarian anarcho-capitalism - is a versatile and continuously differentiated urban texture weaving synergies across multiple overlapping publics. Markets are diversity engines. The more diversity a society contains, the more complex must be its spatial ordering system. The congenial architectural translation of the intricately synergetic programmatic organisation discovered and optimised via profit-and-loss signals within the market process, can be expected from a converging, methodologically geared up architectural discipline that can lead the market. While accepting consumer preferences as final arbiter of the evolutionary trajectory, the expert discourse of architecture among architects is independent of current market demand and offers the opportunity to shape future demand by developing new architectural solutions with potentially compelling advantages. But the argument remains to be made how architecture can deliver new degrees of both order and freedom, not for developers, but for users on the ground. To approach this question it is helpful to loop through architecture’s detractors.

The Revolt Against Architecture

Even in a society without private property territorial demarcations will be a necessary social ordering substrate via access and activity allocations with respectively restricted access and degrees of freedom. Architecture and freedom (just like society and freedom) are thus always already in tension. That is why radical non-conformists like Georges Bataille see architecture as prison, as the enemy.

Georges Bataille writes: “Architecture is the expression of the very being of societies, … that which orders and prohibits with authority, expresses itself in what are architectural compositions. … The storming of the Bastille is symbolic of this state of affairs: it is difficult to explain this impulse of the mob other than by the animosity the people hold against the monuments which are their true masters. … Moreover, the human order is bound up from the start with the architectural order, which is nothing but a development of the former. Such that if you attack architecture, whose monumental productions are now the true masters all across the land, gathering the servile multitudes in their shadow, enforcing admiration and astonishment, order and constraint, you are in some ways attacking man.”5

The radical left wing architectural blogger and polemicist Léopold Lambert – the Funambulist – is building on Bataille’s anti-architecture and anti-establishment approach: “The line is architecture’s representative medium; it creates diagrams of power that use architecture’s intrinsic violence on the bodies to organize them in space. If the white page represents a given milieu — a desert, for example — when an architect traces a line on it, (s)he virtually splits this milieu into two distinct impermeable parts, and actualizes it through the line’s embodiment, the wall.”6 Architecture is identified with the physical operation of the wall as means of control and exclusion: “Each wall creates social conditions on both of its sides: the included and the excluded. One can only be homeless (‘prisoner of the outside’) if there is something called home.”7 As with Bataille the prison becomes the paradigm case for architecture’s social mode of operation: “There is a violence inherent to architecture, which is then necessarily instrumentalized politically: the way we normally build walls is to resist the energy of the body. We then invented devices like doors—a regulator of the wall porosity—and keys, which allow us to establish who can get past architecture’s violence and who cannot. Now, who gets access to the instrument that can transform a regular house into a prison cell is political, but it is not architectural per se to say who gets the key.”

If civilisation depends on architectural ordering, it can’t all be summarily dismissed. Therefore we must introduce the distinction between good and bad ordering, good and bad “violence”. Lambert can avoid this because all the examples and topics he engages with in his blog are extreme or exceptional situations like (suppression of) protests, oppressive social exclusion of marginal groups, war, occupation (as in Gaza) etc., where, especially from a left wing perspective, good vs bad, friend vs enemy in terms of oppressed and oppressor, can be taken for granted without being problematized. So here all architectural “violence” seems obviously bad and is indeed often associated with real violence in the ordinary sense of the word. But on this basis a general theory of the emancipatory or oppressive effects of forms of architectural order cannot be forthcoming.

Robin Evans, “Towards Anarchitecture” is to my knowledge the only text that makes freedom explicitly its central topic.8 An-architecture for Evans means something like non-architecture, he also talks about “the tectonics of non-control”. The first sentence of the article reads: “There is a need to clarify the relationship between ‘architecture’ and human freedom” and the author goes on to claim that he is not interested in any form-symbolism or built metaphor of freedom but in the “direct effect of ‘things’ upon human action”9. His discourse starts with the observation that the physical world offers variable resistance to our freedom of action. He calls this the “resistance of the ambient universe” and emphasizes that the set of possible actions is never complete and that the introduction of new physical systems gives rise to novel action types.

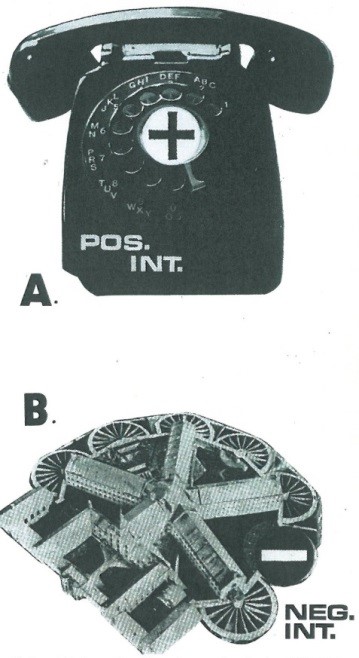

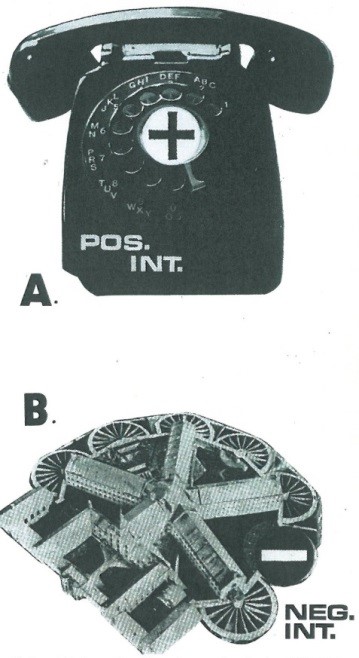

Evans presumes designers to be “committed to providing maximum ‘choice’ or maximum ‘freedom’”10, and also uses the phrase “volitional scope”. He focuses his attention primarily on technical systems’ transformative impact and thus - as Lei Zheng had pointed out in her lecture “Architecture Beyond Form” on Evans’ article11 - anticipated Rem Koolhaas’ later emphasis on the architectural and social impact of technologies like the elevator and air conditioning. I am including Robin Evans here in this chapter against architecture due to his emphasis on architecture’s physical (rather than “symbolic”) operations and due to the examples he chooses to illustrate his points. Just as for Georges Bataille and Léopold Lambert, here too the prison serves as archetypical architecture illustrating architecture’s essential modus operandi. Evans distinguishes positive, freedom enhancing interferences in the system of things, from negative interferences restricting freedom. As example of ‘positive interference’ he cites the telephone network “allowing certain novel actions (instant communications of various kinds) without disallowing any others.”12 He contrasts this with the prison as negative example: ”The walls of the prison, on the other hand, are there for the sole purpose of frustrating certain kinds of action. They are not in themselves meant to provide any positive interference - any expansion of possible action - whatsoever. Their function is to narrow down the scope of action of a given set of persons.”13 As will be further elaborated below, this narrow conception of architectural operations as physically restrictive is leading us astray. The revolt against architecture in the name of freedom is misconceived and futile.

Positive Interference vs Negative Interference. Examples from Robin Evans’ Towards Anarchitecture, Architectural Association Quarterly, January 1970. Caption in Evans’ article reads: Two objects (A,B) are introduced to change the state of the world, but they do so in essentially different ways.

I am more sympathetic when Evans takes a stance against planners and architects “as arbiters of other people’s patterns of life” and is trying to contrast imposing order on living/social systems with imposing order on technical systems, distinguishing ‘software order’ and ‘hardware order’, suggesting that the latter could be substituted for the former, as it were: running a free-wheeling human software on a systematically ordered hardware. Evans is not elaborating this point any further than hinting that the power of hardwired computer networks could promise an answer that leaves human users unshackled.

I would like to pick up his suggestive distinction and idea of a systematic order of things that substitutes for the strict prison-like shackling and channelling of human bodies to achieve social order. Evans’ idea is reminiscent of Friedrich Engels’ inspiring dictum that under communism “the government of persons is replaced by the administration of things”14. However, in contrast to Robin Evans, I believe that brick and mortar architecture can deliver towards this promise of emancipation and does not have to hand the baton to digital technology.

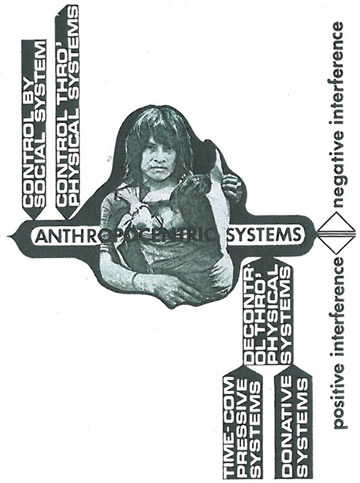

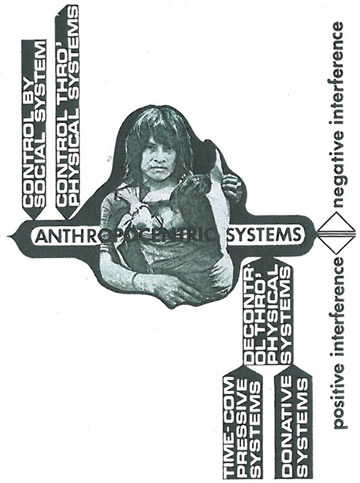

Robin Evans, The Agencies of Control and Decontrol. Evans depicts here Control by Social Systems and Control through Physical Systems as parallel options of Negative Interference. On the positive side he distinguishes Donative systems that add new life content (e.g. Television) and Time Compressive systems (e.g. Vacuum Cleaner) that make activities more efficient. Diagram from Robin Evans Towards Anarchitecture, Architectural Association Quarterly, January 1970

Architecture as Substrate for Social Self-organisation

Now doubt, we are bodies and architecture sometimes physically orders and channels us. But that’s only one aspect of architecture’s social functioning: it also functions as ordering matrix for self-directed browsing and self-sorting. And more importantly, it operates also via thresholds and demarcation lines that do not constitute physical barriers at all, but rather function like signals, indications, and indeed communications. Here architecture works and orders via its information-richness and communicative capacity rather than as if channelling cattle as the prison paradigm suggests. Thus the ‘hard’ architectural ontology of walls, fences, locked gates etc. should de-emphasized and replaced by a ‘soft’ ontology of expressive thresholds, indications, and atmospheres that operate semiologically as guiding orientations, invitations and priming characterisations, in short as language rather than as physically operating apparatus of exclusion.

Frank Gehry, Design for Facebook Headquarters, 2013. The scheme accommodates 2,800 engineers in a single warehouse-like room that distributes, frames, stabilizes and coordinates the collaborative process within a spatial matrix that allows the users to self-sort as participants of various specific social interactions.

Users set free to roam across an intricately ordered matrix of distinctions - for instance in a continuous office landscape as Frank Gehry’s new Facebook campus – might be seen as a compelling instantiation of Engels’ dictum quoted above. To speak of architectural “violence” in this context lacks all plausibility. As violence proper recedes and altogether disappears in the advanced arenas of world society, so does the predominance of physical barriers as spatial ordering mechanisms. Their gradual disappearance from architecture and their substitution by informational architectural operations is a clear sign of societal progress and constitutes a compelling productivity boosting advantage for those institutions that push forward along this trajectory. The simultaneity of inter-aware offerings, the light-footedness of switching between activity and interaction modes, the overall intricacy and dynamism of the cooperative process that motivates the co-location in the first place are all striking advantages of an informational spatial order - which we might term ‘soft order’ - over its physically segregating nemesis ‘hard order’. There is no space here to elaborate further on this concept of an informationally operating, empowering and emancipating architectural order. However, the author has elaborated this theme elsewhere, both with respect to the urban scale and with respect to the architectural and interior scales. With respect to the latter a prior AD article entitled ‘Advancing Social Functionality via Agent Based

Parametric Semiology ‘15 discusses communicative architectural ordering for free agents, especially with respect to activity-based corporate space planning in the context of increasingly self-directed patterns of work and collaboration. With respect to the former, another prior AD article, ‘Hegemonic Parametricism delivers a Market-based Urban Order’16, elaborates how the techniques and values of parametricism can serve to articulate and empower the programmatic order and synergy potentials of market allocated urban co-locations come co-operations . The expectation here is that entrepreneurial freedom, guided by market feedback, is the best premise for delivering sustainable, substantive freedom for all urbanites. To deliver this, architecture must ensure that soft order, built on individual freedom, replaces yesteryear’s hard order.

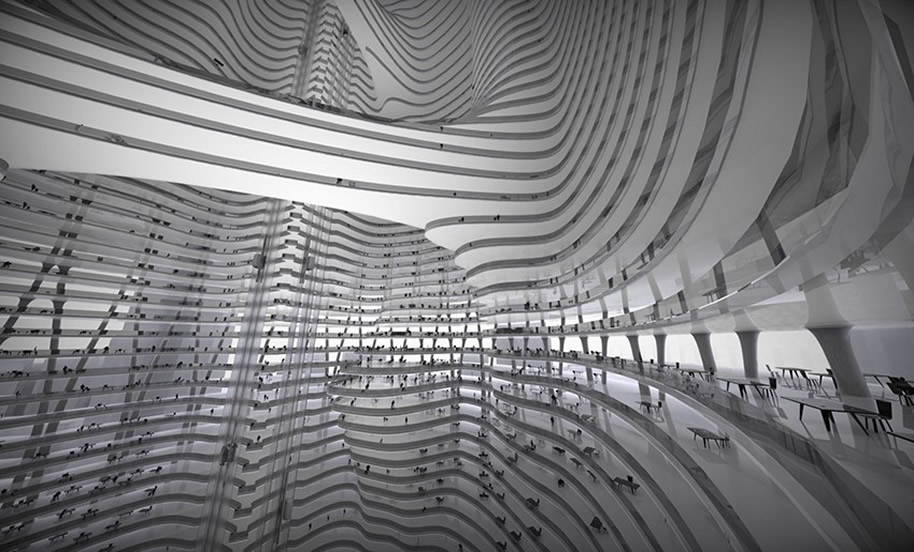

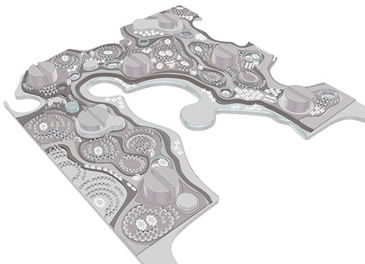

Zaha Hadid Architects, Sberbank Technopark at the Skolkovo Innovation Centre, Moscow, Russia.

The life process of a firm is ordered via rich typology of communicative situations defined by the designed settings/spaces that premise and prime the communicative interactions that are expected to take place within them.

There is yet another aspect - beyond informational guidance - that I would like to include in my concept of ‘soft order’ put forward here, namely the strategic incorporation of vagueness and indeterminacy, i.e. the pursuit of virtuality or ‘the virtual’17. This concept too resides within the orbit of the semiological project: it implies the withdrawal of information, i.e. semiological de-coding rather than encoding. However, this withdrawal of determinate meaning is best achieved not by emptying the space but by filling it with an abundance of unfamiliar, abstract articulations, as so many invitations for creative appropriation by users.

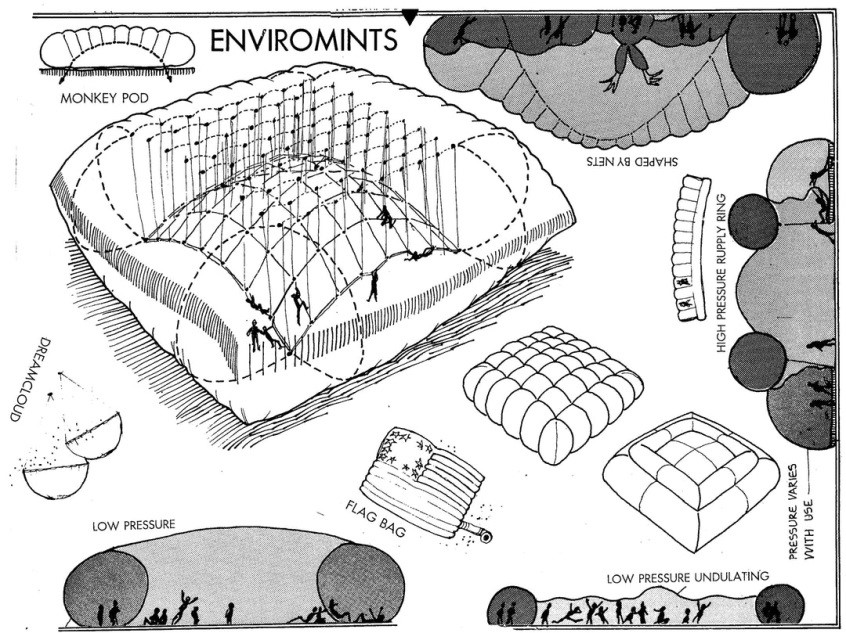

Example of Soft Order: Emanuele Mozzo, Robocrete, public play-scape for courtyard at Università degli Studi di Milano. Diploma project at Studio Hadid/Schumacher, University of Applied Arts, Vienna, 2014. Here spatial differentiations operate as suggestive communications inviting participants’ aleatoric appropriation of the vaguely defined spaces.

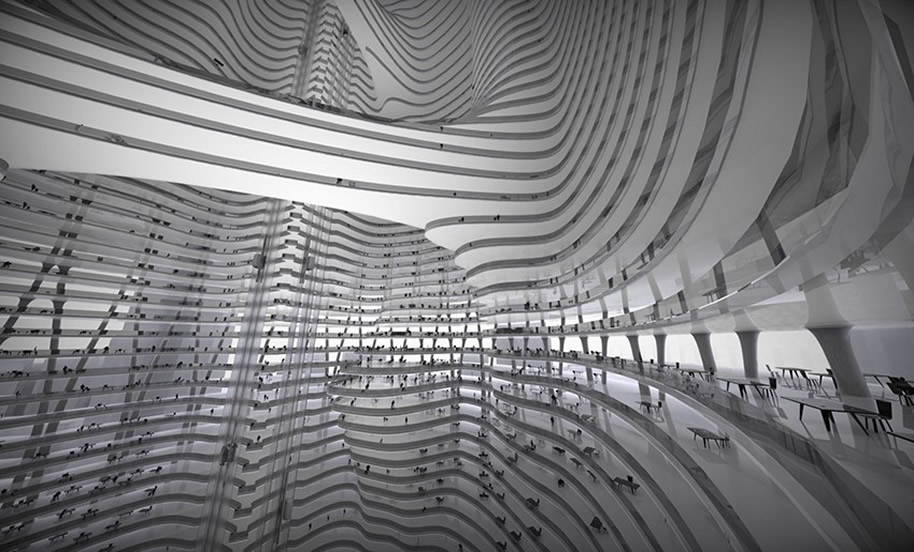

The essential advantage of a soft architectural order, whether determinate or indeterminate, is that it builds on the freedom of self-directed individuals. A second major advantage is that the absence of physical separations via walls allows for an unprecedented density of simultaneous, inter-visible communicative offerings. This makes the construction of a new kind of space possible: the space of simultaneity. To maximally exploit this possibility of total inter-awareness I am promoting the idea of the mega-atrium or hollow building where an internal navigation void replaces the usual solid core that blocks all visual communication. Freedom and awareness of opportunities must increase hand in hand.

Zaha Hadid Architects, Mega-atrium, Competition Design for a new Hyundai Headquarters in Seoul, 2015. The mega-atrium tower as space of simultaneity and maximal interawareness is offered here as a new tower typology well adapted to the communicative requirements of postfordist network society.

1 A slogan of the Bristish 1960s group and magazine ‘Archigram’.

2 Adhocism is the self-explanatory name Charles Jencks gave to a 1960s architectural tendency identified by him in 1972: Charles Jencks, Nathan Silver, Adhocism – The Case for Improvisation, Doubleday & Company, 1972, reprint MIT Press, 2013

3 Daniel C. Dennett, Freedom Evolves, Penguin Books, 2004, p. 44

4 Ludwig von Mises uses the German phrase “Vergesellschaftungsgesetz” which should best be translated as “law of society formation”. However, it has usually been translated as “law of association”. See: Ludwig von Mises, Nationaloekonomie – Theorie des Handelns und Wirtschaftens, Edition Union, Genf, 1940, and: Ludwig von Mises, Human Action – A Treatise on Economics, Yale University Press, 1949

5 Georges Bataille, Architecture (1929), in: Ouvres Completes, Vol.1, pp 171-72, first of 12 vols., Gallimard, Paris 1971-1988

6 Léopold Lambert, THE FUNAMBULIST PAPERS: VOLUME 01, 2013.

7 Who Welcomes this Violence?, Léopold Lambert in conversation with C. Recorded April 2nd, 2015; online: http://www.c-o-l-o-n.com/3_1lambert.html

8 The author was pointed towards Robin Evans’ early and obscure but important contribution via a recent lecture: Lei Zheng, Architecture Beyond Form, lecture given at the AA L.A.W.u.N (Locally Available World unseenNetworks) symposium, Architectural Association School of Architecture, London 2016

9 Robin Evans, Towards Anarchitecture, Architectural Association Quarterly, January 1970, reprinted in: Robin Evans, Translations from Drawing to Building and other Essays, AA Documents 2, p.12

11 Lei Zheng, Architecture Beyond Form, lecture given at the AA L.A.W.u.N (Locally Available World unseenNetworks) symposium, Architectural Association School of Architecture, London 2016

13 Ibid. p.14

14 Friedrich Engels,

Socialism, Utopian and Scientific , Simplicissimus Book Farm, 1901, original German: Die Entwicklung des Sozialismus von der Utopie zur Wissenschaft, 1883

15 Patrik Schumacher, Advancing Social Functionality via Agent Based Parametric Semiology , Published in: AD Parametricism 2.0 – Rethinking Architecture’s Agenda for the 21st Century, Editor: H. Castle, Guest-edited by Patrik Schumacher, AD Profile #240, March/April 2016

16 Patrik Schumacher, Hegemonic Parametricism delivers a Market-based Urban Order, Published in: AD Parametricism 2.0 - Rethinking Architecture’s Agenda for the 21st Century, Editor: H. Castle, Guest-edited by Patrik Schumacher, AD Profile #240, March/April 2016

17 See: John Rajchman, The Virtual House, Any Magazine No. 19/20, 1997; also: Brian Massumi, Sensing the Virtual, Building the Insensible, in AD: Hypersurface Architecture, 1998

back to WRITINGS